Spectacle chant, musique et danse Soufie d'Egypte avec Sheikh Ahmad Al Tuni et ses musiciens - Tarab

Publié le 13 Octobre 2008

Ce message m'a été envoyé par un visiteur grâce au formulaire de contact accessible en bas de page de mon blog que j'ai quelque peu agrémenté.

C'est toujours par la musique qu'on peut accéder à l'irréel. Qu'il s'agisse de Mozart, de chants grégoriens ou de chants soufis, la musique reste le moyen d'atteindre le spirituel. Dans la philosophie Soufie, le chant et la voix, jouent le rôle du passeur entre l'homme et Dieu.(1).

Spectacle chant, musique et danse Sufi d'Egypte avec Sheikh Ahmad Al Tuni et ses musiciens

Tarab

MuziekPublique et Tarab présentent

« Al Wegdann » الوجدان

« De tout mon être… »

Bruxelles, jeudi 13 novembre et vendredi 14 novembre, 20h00

Spectacle de musique, chant et danse Sufi de Haute Egypte

avec Sheikh Ahmed Al-Tûni et sa troupe de 6 musiciens - Béatrice Grognard et quelques danseuses de sa troupe Tarab.

La chorégraphe et danseuse Béatrice Grognard retrouve le charismatique chanteur Sufi Sheikh Ahmad Al-Tûni pour un spectacle unique !

Jamais auparavant, le répertoire du Sheikh Tuni n’a été magnifié par le mouvement artistique, dansé et féminin.

Ahmad Al-Tûni est l’un des derniers grands chanteurs Soufis de Haute Egypte. Sa renommée aujourd’hui dépasse largement l’Egypte. Accueilli sur les scènes internationales, sa voix s’élève et provoque la transe soufie, rite antique pour toutes et tous. Ouvert, créatif, il exprime un large éventail de comportements émotionnels, Ahmad al-Tûni, entouré de ses musiciens, chante, mime avec expression sa poésie. Le balancement de son corps ponctue la virulence rythmique du daff (un des plus anciens tambours sur cadre en Asie et en Afrique du Nord), du riqq et de la tabla d’Egypte. Il est originaire du village de Hawatka près d’Assiout. Il est un des plus grands munshids d’Egypte avec Sheikh Yasîn al-Tuhâmi et Sheikh Ahmad Barrayn. Dans ses poésies, on retrouve les images et symboles d'une mystique peuplée de multiples océans et mers, dans lesquelles le poète aimerait tant s'immerger, océan de plénitude ou de connaissance, mer de la volupté, tourbillon du temps et de cette autre vie inaccessible. (Les Orientales).

La renommée d’Ahmad al-Tûni ne tarde pas à dépasser le seul territoire égyptien. En 1998, le film Vengo de Tony Gatlif s’ouvre sur sa rencontre avec Tomatito, maître de la guitare flamenco. En 1999, il est invité pour la première fois en France, au Théâtre de la Ville, et enregistre Le Sultan de tous les munshidîn. Depuis, Cheikh Ahmad al-Tûni est reconnu sur les scènes internationales.

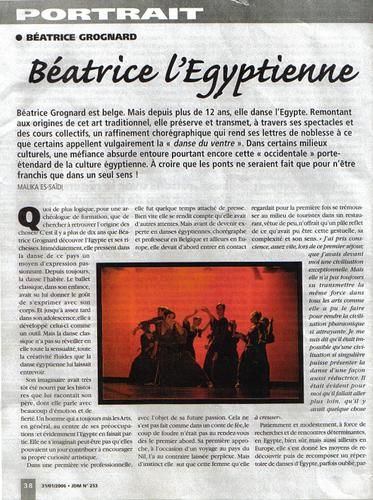

Béatrice Grognard est une archéologue belge. Au cours d’un voyage en Egypte, elle découvre les danses classiques et populaires du payx. Pour elle, l'art se caractérise par un jeu théâtral flamboyant, une émotion et une expression dansée tantôt intérieures, tantôt puissantes et proches de la transe. La danse Sufi vous sera ici dévoilée avec justesse et splendeur, vous emportant jusque dans les tourbillons de la danse sacrée des derviches. Elle a fondé au Caire « Tarab » , l’école des danses populaires et classiques d’Egypte.(source)

Ensemble, ces deux artistes célèbreront l’amour divin et humain, l’allégresse extatique, le désir, la passion douce ou acide, la souffrance de la rupture, l’angoisse de l’absence, le renoncement et le sentiment d’abandon du corps et de l’esprit.

Lieu : Muziekpublique, Théâtre Molière

Galerie de la Porte de Namur

3 Square du Bastion

1050 Ixelles (Bruxelles)

Tickets :

10 € pour les membres Muziekpublique

16 € pour les non membres

13 € en pré vente

Réservation : par un versement sur le compte de MuziekPublique,

n°433-1187021-57, avec, en communication, le nombre de places et le jour souhaités.

e-mail : info@muziekpublique.be

Notes

particular brotherhood (tariqa). It includes the hadra, that moment of collective spirituality, where the common man can enter into the presence of the divine; this is an open, creative event where a whole range of emotional behaviour is expressed. No matter whether one is a disciple of Ahmad Al-Badawi, the founder of the Egyptian way known as the Ahmadiyah, or a member of the Shadhiliyah, the brotherhood created by Abu Al-Hasan Al-Shadili from Fez in Morocco, or a member of Ahmad Al-Rifa'i'rifa'iyah brotherhood, founded in Southern Irak in the 12th century, everyone flocks towards the sound of the munshid's voice. he is the true master of ceremonies, he will throw forth several spirited phrases guaranteed to charm and win over his public in exactly the way he wants.

The inshad or sacred chant is the central pillar of organisation here. In this context, where there are absolutely no authoritarian or religious sanctions from on high banning music and emotion, it is the munshid who controls everything, and and as a result the inshad is both freer and all the richer in musical terms.

Generally speaking, the religious singing of today recalls Arab music in urban style from before the 30's. This fact has been drawn to our attention by Michael Frishkopf. A small mixed instrumental group (the takht) in which each instrument is allowed to keep its individuality and express it in richly ornamented style, a flexibility of form that can include vocal and instrumental improvisations, the inclusion of some deliciously sensual modulations that float from one mode (maqam) to another, the whole punctuated with melodic rhythms (qafla-s): these are the traits that give this particular style its inherent richness.

So little by little the munshid has built up his ensemble and its musical potential. Thus we find the instruments originally linked to this type of singing the daf, the naqrazan (a percussive copper drum to be struck with sticks) the raq (a little tambourine with tiny cymbals attached) or the qawal (the flute) this is the instrumentation still used by Shaykh Barrayn but others have started to make a timid appearance, too: the Egyptian tabla, for instance, the kamantcha (the oriental violin), the 'ud and even occasionally the qanun. the musicians who perform on these instruments are not necessarily great virtuosi in the classical or strict sense of the term, but rather than being masters of a technique, one senses their devotion, their desire to amplify and serve the voice of the singer.

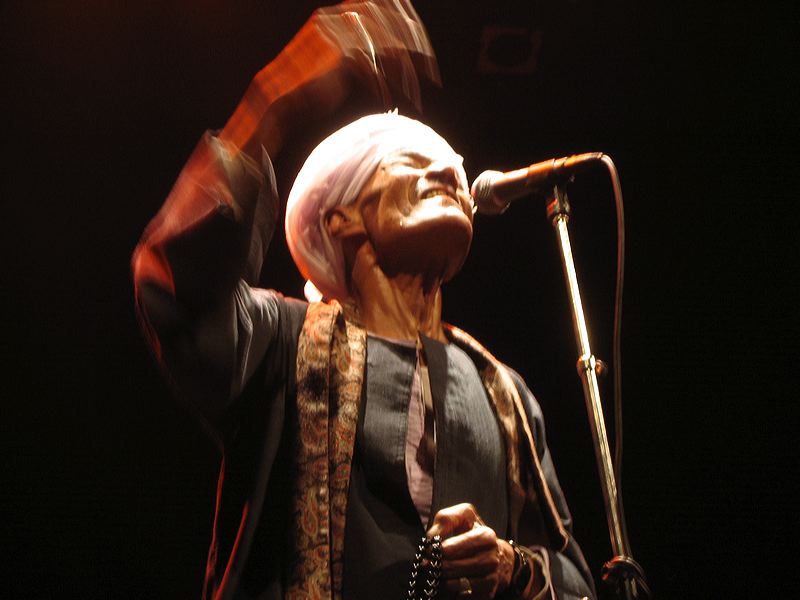

The great Egyptian munshid Ahmad Al-Tuni, a master of the inshad, chants almost in the manner of an actor from earlier times declaiming his lines. He holds his sipa (the muslim rosary) in one hand and accompanies his poetry with expressive gestures and mime; his body moves nervously to and fro, from side to side, as if to mark the violently forceful rhythms of the daf and the Egyptian tabla. he recalls better than anyone those singers of former times known as the mutrib, literally "one who creates tarab", the singers who produced the ideal blend of emotion from the mingling of words and voice.

particular brotherhood (tariqa). It includes the hadra, that moment of collective spirituality, where the common man can enter into the presence of the divine; this is an open, creative event where a whole range of emotional behaviour is expressed. No matter whether one is a disciple of Ahmad Al-Badawi, the founder of the Egyptian way known as the Ahmadiyah, or a member of the Shadhiliyah, the brotherhood created by Abu Al-Hasan Al-Shadili from Fez in Morocco, or a member of Ahmad Al-Rifa'i'rifa'iyah brotherhood, founded in Southern Irak in the 12th century, everyone flocks towards the sound of the munshid's voice. he is the true master of ceremonies, he will throw forth several spirited phrases guaranteed to charm and win over his public in exactly the way he wants.

The inshad or sacred chant is the central pillar of organisation here. In this context, where there are absolutely no authoritarian or religious sanctions from on high banning music and emotion, it is the munshid who controls everything, and and as a result the inshad is both freer and all the richer in musical terms.

Generally speaking, the religious singing of today recalls Arab music in urban style from before the 30's. This fact has been drawn to our attention by Michael Frishkopf. A small mixed instrumental group (the takht) in which each instrument is allowed to keep its individuality and express it in richly ornamented style, a flexibility of form that can include vocal and instrumental improvisations, the inclusion of some deliciously sensual modulations that float from one mode (maqam) to another, the whole punctuated with melodic rhythms (qafla-s): these are the traits that give this particular style its inherent richness.

So little by little the munshid has built up his ensemble and its musical potential. Thus we find the instruments originally linked to this type of singing the daf, the naqrazan (a percussive copper drum to be struck with sticks) the raq (a little tambourine with tiny cymbals attached) or the qawal (the flute) this is the instrumentation still used by Shaykh Barrayn but others have started to make a timid appearance, too: the Egyptian tabla, for instance, the kamantcha (the oriental violin), the 'ud and even occasionally the qanun. the musicians who perform on these instruments are not necessarily great virtuosi in the classical or strict sense of the term, but rather than being masters of a technique, one senses their devotion, their desire to amplify and serve the voice of the singer.

The great Egyptian munshid Ahmad Al-Tuni, a master of the inshad, chants almost in the manner of an actor from earlier times declaiming his lines. He holds his sipa (the muslim rosary) in one hand and accompanies his poetry with expressive gestures and mime; his body moves nervously to and fro, from side to side, as if to mark the violently forceful rhythms of the daf and the Egyptian tabla. he recalls better than anyone those singers of former times known as the mutrib, literally "one who creates tarab", the singers who produced the ideal blend of emotion from the mingling of words and voice.

/http%3A%2F%2Fi42.tinypic.com%2F206c4mx.jpg)

Voir aussi

Hadra : rituel collectif du Dhikr

Présentation dans le journal du Mardi

/image%2F1043068%2F20190307%2Fob_c9e249_lnolno-last-night-in-orient-le-log.png)

/image%2F1043068%2F20190613%2Fob_027ab2_last-night-in-orient-1.png)